If you are an IB Psychology student, you know the struggle of distinguishing between the endless list of terminologies in Paper 3. Is credibility the same as reliability? What exactly is the difference between theoretical and snowball sampling? These aren’t just vocabulary words; they are the critical lenses through which you must evaluate studies to score high marks.

Whether you are analyzing a case study on London taxi drivers or dissecting a qualitative interview on happiness, understanding Psychology Research Methods is non-negotiable. In this guide, we will break down the most confusing concepts—sampling, generalizability, validity, and bias—using real-world examples and clear definitions to ensure you walk into your exam with confidence. At Easy Sevens Education, we believe in turning abstract theories into concrete marks.

The Foundations of Research: Qualitative vs. Quantitative

Before diving into specific terms, it is crucial to understand the landscape. In IB Psychology, you are often juggling two worlds: the strict, variable-controlled world of quantitative research (Paper 1 & 2) and the rich, interpretive world of qualitative research (Paper 3).

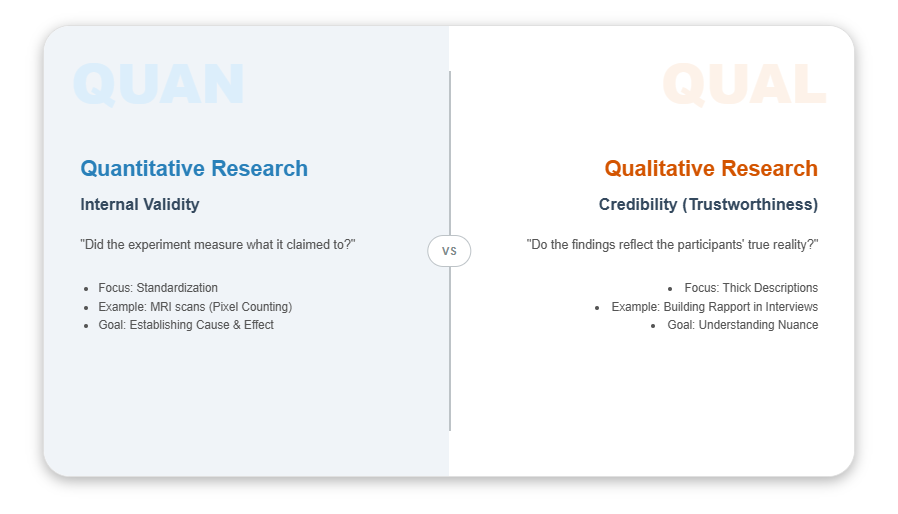

In quantitative studies, such as the famous MRI scans of taxi drivers, researchers look for standardization. They want to know if the size of the hippocampus changes based on spatial navigation experience. Here, we care about internal validity—did the experiment actually measure what it claimed to, or did a confounding variable interfere?

In contrast, qualitative research focuses on credibility and trustworthiness. If you are studying a hospital with mostly elderly patients, you aren't just looking for numbers; you are looking for "thick descriptions"—rich, detailed accounts that provide context to the behavior. As noted in recent tutoring sessions, "thick descriptions" are vital because they allow the researcher to capture the nuance of the participants' experiences, rather than just a simple score.

Key Concepts Comparison

To help you visualize the differences, here is a breakdown of how similar concepts apply differently depending on the research focus.

| Concept | Definition & Application | Example from Review |

|---|---|---|

| Credibility (Trustworthiness) | The qualitative equivalent of internal validity. It asks: Do the findings reflect the participants' true reality? | Establishing a rapport with participants so they answer honestly rather than giving "socially desirable" answers. |

| Construct Validity | How well an abstract idea is measured. | If you measure "happiness" by how much someone smiles, that may have low construct validity. A smile doesn't always equal happiness. |

| Spurious Correlation | A relationship between two variables that is actually caused by a third factor or random chance. | "Eating ice cream makes trucks crash into rivers." (Both happen in summer/hot weather, but one does not cause the other). |

| Triangulation | Using multiple methods, researchers, or theories to increase credibility. | Checking results using both interviews and observations (Method Triangulation). |

Deep Dive: Sampling, Generalizability, and Bias

1. Decoding Sampling Methods

Sampling is how you select your participants. In Paper 3, identifying the specific type of sampling is often the first step in your evaluation.

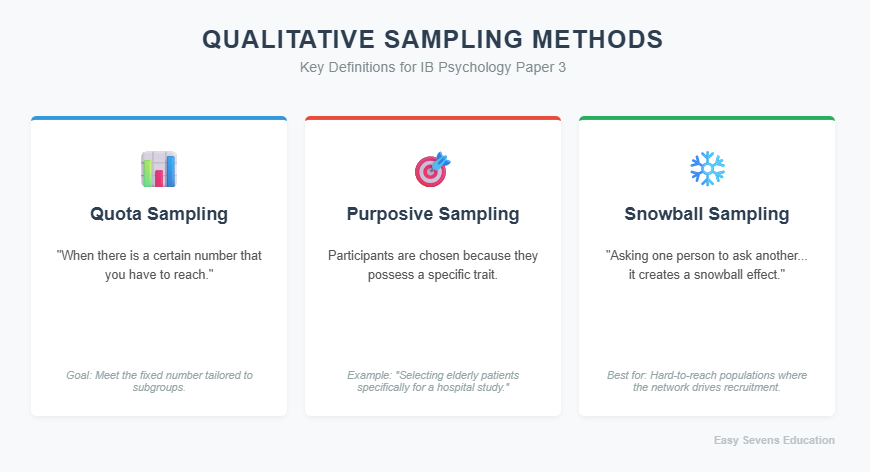

- Quota Sampling: This is when there is a specific number (quota) you need to reach for different sub-groups. Once that number is met, you stop recruiting.

- Purposive Sampling: Participants are chosen because they possess a specific trait relevant to the study. For example, if you are doing a study on a hospital, you might specifically target elderly patients because they are the ones getting sick. You have a "purpose" for that sample.

- Snowball Sampling: This is the "network" effect. You ask one participant to recommend another, and they ask another. It doesn't necessarily mean the researcher is demanding it; it’s just that "it just happens," like a rolling snowball gathering mass. This is useful for hard-to-reach populations.

2. The Three Types of Generalizability

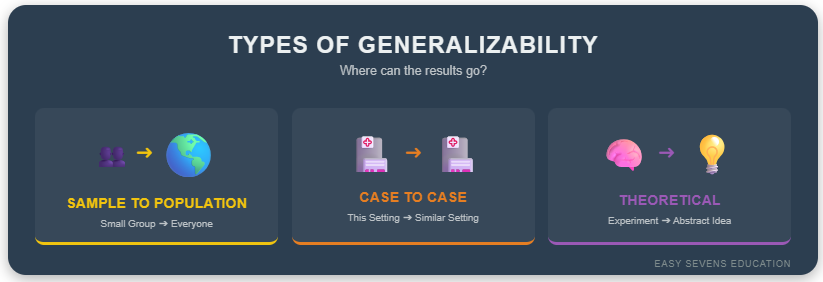

Students often think generalizability just means "does this apply to everyone?" However, in qualitative research, we break it down into three specific categories:

- Sample-to-Population Generalizability: The classic definition. Can the findings from this specific group be applied to the larger target population?

- Case-to-Case Generalizability: Transferability. Can the findings from this specific case (e.g., a high-stress office environment) be applied to another similar case (e.g., a different high-stress corporate team)?

- Theoretical Generalizability: This is often the hardest to remember. It refers to how well the findings can be applied to develop a broader theory or concept. For instance, if a study explores the concept of "resilience," do the results help us understand the theory of resilience better?

3. Navigating Bias

Bias threatens the validity of any study. Here are the ones you need to watch out for:

- Confirmation Bias: This occurs when a researcher has a preconceived notion and unintentionally "cherry-picks" data to fit that motion. As discussed in our sessions, it's like learning new information but your brain filters it to confirm what you already believed.

- Social Desirability Effect: Participants may lie or alter their behavior to look good. If you ask people about their charitable habits, they might exaggerate to appear more altruistic.

- Acquiescence Bias: The tendency for participants to just say "yes" or agree with the researcher, regardless of their actual feelings.

- Selection Bias: If you study "office work ethics" but only conduct the experiment within your own department, your selection is biased. You aren't getting a representative view of all office workers.

4. Reflexivity: The Researcher’s Check

Reflexivity is a solution to researcher bias. It involves the researcher reflecting on their own background, biases, and influence on the study. A "reflexive" researcher might ask: "Did my presence as an authority figure influence how these students answered?"

Related Resources

Mastering these terms is just the beginning of your IB Psychology journey. To fully prepare for your internal assessments and final exams, you need a structured approach to both content and application.

If you are looking for more support, check out our guides on IB Psychology Tutors who can help you refine your IA. Additionally, for those struggling with the broader demands of the diploma, our IB English Tutors can assist in transferring these critical thinking skills across subjects.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between internal and external validity?

Why is "thick description" important in qualitative research?

What is the "WEIRD" sample bias?

How does triangulation increase credibility?

What is theoretical sampling?

Conclusion

Psychology research methods can feel like a maze of terminology, but mastering them is the key to unlocking high scores in Paper 3. Remember, theoretical vs. snowball sampling isn't just about memorizing definitions; it's about understanding how researchers gather data. Credibility isn't just a buzzword; it's the standard by which we judge if a qualitative study is worth listening to.

When you are revising, don't just read the definitions—apply them. Ask yourself: "Does this study have high construct validity? Is there a threat of social desirability here?" If you can think critically about these concepts, you are well on your way to a 7.

Need help structuring your revision or understanding complex studies? Contact Easy Sevens Education today to work with expert tutors who can simplify the syllabus and help you succeed.