Your writing hand throbbing. Your brain feeling like a fried circuit board after hours in the exam hall. Sound familiar? If you were one of the many students tackling the IB Psychology Higher Level exams in May 2025, you know the feeling. These exams aren’t just tests of psychological knowledge; they’re tests of endurance – physical and mental.

Across IB forums and student communities, the May 2025 Psychology HL papers sparked intense discussion. Students shared anxieties, celebrated perceived wins, debated tricky questions, and commiserated over punishing schedules. Our IB Psychology tutor dives deep into those conversations, offering insights and clarifying points based on the collective experience of the M25 cohort. Whether you’re an M25 student reflecting on the experience or an M26 preparing for your turn, understanding these key takeaways is invaluable.

The Back-to-Back Battle: When Psychology Meets English

One of the most prominent points of contention wasn’t the content of the exams themselves, but the relentless scheduling. Many students faced the daunting prospect of sitting for multiple demanding HL exams – often Psychology Papers 1 & 3 followed immediately by English Language & Literature or Literature Paper 1 – with minimal or no breaks in between.

Imagine transitioning directly from dissecting psychological studies and qualitative research methods to crafting analytical essays on literary texts. This physical and cognitive shift, undertaken after hours of intense writing, left many students feeling utterly drained. Comments flooded in about traumatised hands, cramping fingers, and the sheer exhaustion of writing for six, seven, or even eight hours straight. Even students with extra time or rest breaks reported feeling the pressure, often with limited time between papers despite accommodations. This scheduling crunch highlights a significant challenge in the IB system – the need for intense focus and output across disparate subjects in rapid succession.

IB Psychology May 2025 Paper 1: Surprises, Specifics, and SAQ Stress

Paper 1, covering the Core Approaches (Biological, Cognitive, Sociocultural), often sets the tone. For the May 2025 session, reactions were mixed. Some found it “blessed” due to the absence of certain predicted topics like extensive research methods or ethics questions in the main SAQs. However, specific questions sparked considerable debate and anxiety.

The Working Memory Model (WMM): Many students expressed surprise and frustration at a specific SAQ asking about the Working Memory Model. Some had focused on other models like the Multi-Store Model (MSM) or felt unprepared for a question solely on WMM. This underscores the importance of studying all key models within an approach, even those perceived as less likely to appear. For example, a student might have diligently studied Loftus and Palmer for reconstructive memory or Glanzer and Cunitz for MSM, only to be tested on the nuances of the phonological loop or visuospatial sketchpad.

Enculturation Phrasing: A seemingly simple SAQ on enculturation caused widespread confusion. The debate centered on whether the question asked for the “effect on enculturation” or the “effect of enculturation” on cognition or behaviour. This slight difference in wording drastically changes the required focus. “Effect of enculturation” asks how culture shapes an individual’s thoughts or actions (e.g., Fagot’s study on gender roles). “Effect on enculturation” is a less common phrasing that could imply factors influencing the process of cultural transmission itself. This grammatical ambiguity left many second-guessing their entire response, highlighting the critical need for careful reading of question prompts.

Agonists and Antagonists: The biological SAQ involving agonists or antagonists also proved challenging for some. While many understood the core concept of neurotransmitters and receptor sites, identifying specific examples like Tryptophan (a serotonin precursor, not an agonist itself) or linking appropriate studies (like Crockett et al. on serotonin and prosocial behaviour, or studies involving acetylcholine antagonists like Scopolamine) tripped up others. It served as a reminder that understanding the mechanism of neurotransmitter action and having specific, applicable study evidence is crucial. For instance, simply knowing that SSRIs affect serotonin isn’t enough; you need to articulate how (e.g., by blocking reuptake, increasing serotonin levels in the synapse, thus acting indirectly).

Biological ERQ: The biological extended response question (ERQ), particularly the HL extension on the relationship between the brain and behaviour (potentially involving animal studies), was unexpected for some. This reinforced that students must prepare for the full scope of the syllabus, including extensions, and be ready to apply studies across different contexts.

IB Psychology May 2025 Paper 2: Navigating the Optional Themes

Paper 2, focusing on the optional themes (Abnormal, Developmental, Health, Human Relationships, Sport, Qualitative), generally received more positive feedback, although specific questions still posed difficulties.

Varied Experiences: Students who felt their preparation aligned well with the specific questions for their chosen theme reported feeling confident. For example, those who had thoroughly studied the validity and reliability of diagnosis in Abnormal Psychology found the question quite accessible, able to apply multiple relevant studies.

“One or More” Clarification: A common point of relief and discussion was the phrasing “one or more” in questions, particularly in Health Psychology (e.g., concerning health problems) and Human Relationships. Students correctly deduced that this wording explicitly allows focusing on a single issue or study in depth, as long as the response is comprehensive and meets the other criteria (using studies, evaluation). For instance, discussing various psychological explanations for stress using studies like Kiecolt-Glaser et al. would fully satisfy a “one or more” requirement even if no other health problem was mentioned.

Tricky Applications: Some questions required nuanced application of studies. For instance, in Human Relationships, debating the applicability of attachment studies like Hazen and Shaver to adult romantic relationships or using studies like Bradbury and Fincham required careful justification. Similarly, the Developmental Psychology question on biological factors impacting cognitive/social development needed studies that explicitly linked biological elements (like genes or hormones) to developmental outcomes, not just general resilience studies.

IB Psychology May 2025 Paper 3: The Qualitative Conundrum

Paper 3, the qualitative research paper based on a stimulus text, often presents unique challenges. The May 2025 paper, focusing on interviews about mental health experiences in Europe, was no exception, sparking significant debate on methodology and interpretation.

Research Method: Focus Group vs. Interview? The most heated discussion revolved around identifying the primary research method. The stimulus described “interviews” with “6-12 people” and mentioned facilitators guiding the discussion while also allowing for personal sharing. This led to two main camps:

Focus Group: Arguments included the group setting (6-12 people per session) and the emphasis on creating a safe space for shared discussion, characteristic of focus groups.

Semi-Structured Interview: Arguments highlighted the presence of a facilitator with a guide of questions and the mention of facilitators using discretion to move to more personal questions, fitting the definition of a semi-structured approach, even if conducted with multiple people simultaneously (which can sometimes occur, or the text might have implied multiple semi-structured interviews within each country).

Key Takeaway: The ambiguity suggested the IB might accept either answer if supported by specific evidence from the stimulus text. A strong answer would draw characteristics from the text – like the group size, the role of the facilitator, the purpose of the sessions – and link them clearly to the chosen method. For example, stating it was a semi-structured interview and citing the facilitator’s guide and discretionary questioning, OR stating it was a focus group and citing the group size and emphasis on safe, shared discussion.

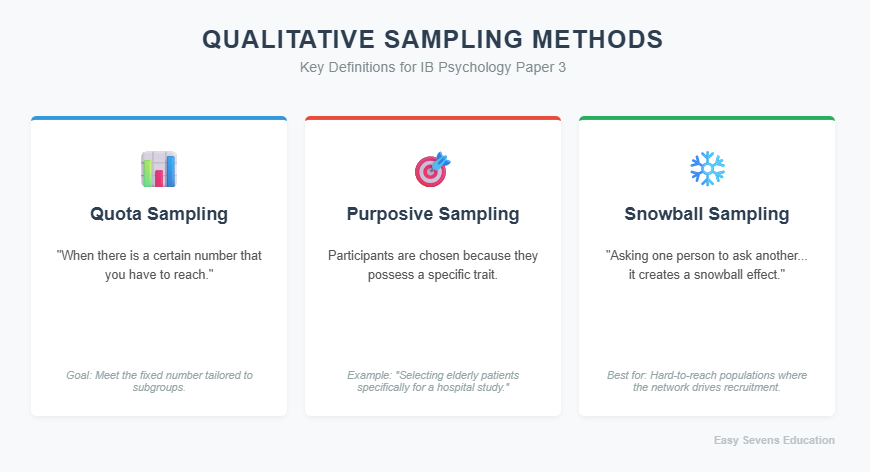

Sampling Method Confusion: Identifying the sampling method also proved difficult, with students suggesting everything from purposive, opportunity, snowball, quota, stratified, to selective sampling.

Purposive Sampling: Many concluded this was the most likely method, as participants were specifically selected based on having mental health problems and receiving treatment, aligning with the study’s aim.

Opportunity Sampling: Some argued this was plausible if participants were chosen based on their easy accessibility to the researchers or facilitators.

Snowball Sampling: While mentioned, this was largely dismissed as the text didn’t describe participants recruiting other participants.

Quota Sampling: Suggested by some due to the mention of a specific number of participants (e.g., 73), but typically involves recruiting specific numbers within subgroups based on characteristics.

Key Takeaway: Similar to the research method, the best approach was to justify the chosen sampling method using evidence from the stimulus text describing how participants were recruited or selected. Purposive seemed the strongest fit given the criteria mentioned for participation.

The “Transferability” Challenge: Question 3, asking about “transferability” of the findings, stumped many. Students familiar with quantitative research might expect questions on “generalizability.” Transferability is the qualitative research equivalent of generalizability. It asks how applicable the findings are to other contexts or populations.

Explanation: Unlike quantitative generalizability based on statistical probability and representative samples, transferability in qualitative research relies on providing rich, detailed descriptions (“thick description”) of the participants, context, and findings. This allows the reader to judge whether the findings might “transfer” to their own situation or a different context.

Applying to the Stimulus: Valid points raised by students included discussing limitations imposed by the sample (e.g., limited to European countries, specific types of mental health problems, those receiving treatment), the sample size, the sampling method (purposive samples are not designed for statistical generalizability), and potential biases (e.g., cultural bias). Discussing how providing rich detail or using triangulation could enhance transferability were also relevant points. Simply talking about reliability or validity without linking explicitly to transferability or the qualitative nature of the study might not earn full marks.

Additional Research Methods: The question asking for an alternative or additional research method also required careful consideration of what would complement or provide different insights alongside interviews/focus groups. While various methods were suggested, the most appropriate would be other qualitative methods (like observation or case studies) or potentially quantitative methods (like surveys) if the student justified how this would add value to the existing qualitative data (e.g., providing prevalence rates or correlating variables mentioned in the interviews). Suggesting an experiment, for instance, would be less applicable to exploring lived experiences of mental health treatment.

Looking Ahead: Grade Boundaries and Lessons Learned

The overall feeling post-Psych HL exams was a mix of relief, exhaustion, and uncertainty. The perception of the papers’ difficulty varied widely, from “amazing” and “blessed” to “cooked” and “brutal.” This divergence suggests that students’ preparation strategies and strengths played a significant role.

The common sentiment among those who found the papers manageable was a concern for higher grade boundaries. While the IB does adjust boundaries based on global performance, focusing on your own effort and output is key.

For current and future IB Psychology HL students, the May 2025 experience offers crucial lessons:

Read Questions Meticulously: Pay close attention to every word, especially in SAQ prompts (“effect of” vs. “effect on,” “agonist” vs. “antagonist,” “one or more”).

Cover All Syllabus Areas: Do not neglect seemingly less likely topics or models (like WMM if you favour MSM) or HL extensions (like specific biological applications or animal studies).

Understand Research Methods & Ethics Deeply: These concepts are fundamental and can appear in various forms across all three papers, including applied questions in Paper 3. Understand the nuances of qualitative methods and their evaluation criteria (like transferability).

Master Study Application: Be able to apply studies flexibly to different questions and evaluate them critically. Know why a study is relevant to a specific concept.

Practice Timed Writing: The sheer volume of writing under time pressure is a significant challenge. Practice completing papers within time limits, especially back-to-back if your school schedule mimics this.

Prioritise Well-being: The exam period is a marathon. Build in strategies for managing stress, getting enough rest, and taking short breaks, even during intense exam days.

Ultimately, the May 2025 IB Psychology HL exams were a significant milestone for the M25 cohort. The shared experience, debated questions, and collective relief highlight the challenging yet rewarding journey of studying psychology at the Higher Level in the IB Diploma Programme.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

The main debate was whether the research method described in the stimulus text was a focus group or a semi-structured interview. Students argued for both based on details like the group size (6-12 people), the presence of a facilitator, and the mention of an “interview guide” versus group discussion characteristics.

While several methods were suggested, purposive sampling was widely considered the most likely correct answer. This is because participants were specifically selected based on criteria relevant to the study’s aim (having mental health problems and receiving treatment).

Transferability is the qualitative research equivalent of generalizability. It refers to the extent to which the findings of a qualitative study can be applied or “transferred” to other contexts or populations. This is assessed based on the richness of the data and description provided, not statistical representativeness.

Yes, absolutely. The phrasing “one or more” explicitly means you can choose to focus on just one health problem, study, or example. Your response will be assessed on the depth and quality of your discussion for that single focus, not the number of topics covered.

The question likely required discussion of the Working Memory Model itself, explaining its components and function. Studies directly investigating specific aspects or components of the WMM (like studies on dual-task performance or the capacity of working memory stores) would be most relevant. Studies used for other memory models like the Multi-Store Model (e.g., Milner’s HM case study for memory localization or Glanzer and Cunitz for MSM stores) would generally not be appropriate for a question specifically on WMM.

Yes, in the IB Psychology exam, it is generally acceptable to use the same study in different questions on the same paper (often referred to as “double-dipping”), provided the study is relevant and applied correctly to each specific question’s demands.

If the overall performance of the global cohort is stronger than in previous years (suggesting the papers were perceived as easier on average), the grade boundaries for each grade level (1-7) may be slightly higher. Conversely, if performance is weaker, boundaries might be lower. The IB adjusts boundaries annually based on student performance to maintain standards.